Deep Energy Retrofits , Energy Efficient Stuff , Low Energy Housing

Being Visionary in Bridgewater, Nova Scotia

Here’s a success story that is dear to my heart: Bridgewater, NS. Ten years ago, my biz partner and I approached Leon de Vreede, Sustainability Planner for Bridgewater, about an idea for a deep energy retrofit program for houses to be piloted in Bridgewater. We knew his title would make our idea interesting. He liked it, and we worked up a presentation for council, but, well, it was a little too early in their process for anyone to buy in. Truth be told, it was also too early in our process.

Fast forward to 2017, and now, we’re involved with Clean Net Zero, a Deep Energy/Net Zero Retrofit project headed by Clean Foundation, funded by Natural Resources Canada, and ‘hosted’ by the Town of Bridgewater.

Looking to the Future

Clean Net Zero is happening in Bridgewater because there’s vision there. Lots of vision. Plus passion, intelligence, and political will. The town has a 35-year energy plan in place. Here’s some current results from that plan, published on cbc.ca, 1 Dec 2017:

Targets set in 2013, to be met by 2019:

- Energy consumption for Municipal buildings reduced by 25%

- Greenhouse gas emissions from Municipal buildings reduced by 25%

Results in 2017:

- Only 4% more reductions in energy consumption to meet 2019 target

- Greenhouse gas emissions cut by 31% already.

The Town has saved CAD$200,000 in energy costs.

Looking Past Bridgewater

It looks like Leon de Vreede, his team and town council have developed a blueprint for a successful long range energy plan for municipalities. Here’s proof:

Bridgewater Mayor, David Mitchell, attended the Michelin Cities conference in France (Nov 25 – Dec 1 2017). The conference hosts all the communities in the world that have a Michelin plant. He gave a presentation there on the Energize Bridgewater program and sent this news back to his team:

“This afternoon I attended an international press conference of the Mayors for the network of Michelin cities. Media was there from all over the world. This is a direct quote from the delegate from India.

Never did I think I would come to this conference representing the eight million people of my city and have one of our major problems solved by the town of Bridgewater with only 8500 people but their energy plan did just that…

The Energize Bridgewater session was the most well attended of the sessions and from India to Oklahoma, they have questions and see solutions in our plan. We should all be proud of this. It proves the plan is solid. That our community is on the right path and that we will be a resource for the globe going forward. I cannot tell you how proud I am to represent Bridgewater.”

Way to represent, Mayor Dave!

About the Author

Shawna Henderson is CEO of two companies: Blue House Energy, providing online training for the homebuilding industry, and Bfreehomes Design, providing research, design, and consulting services for Net Zero Energy new construction and retrofit projects in Atlantic Canada and beyond.

There are several approaches to designing or specifying a sustainable house.

The first thing to do is clarify some terms.

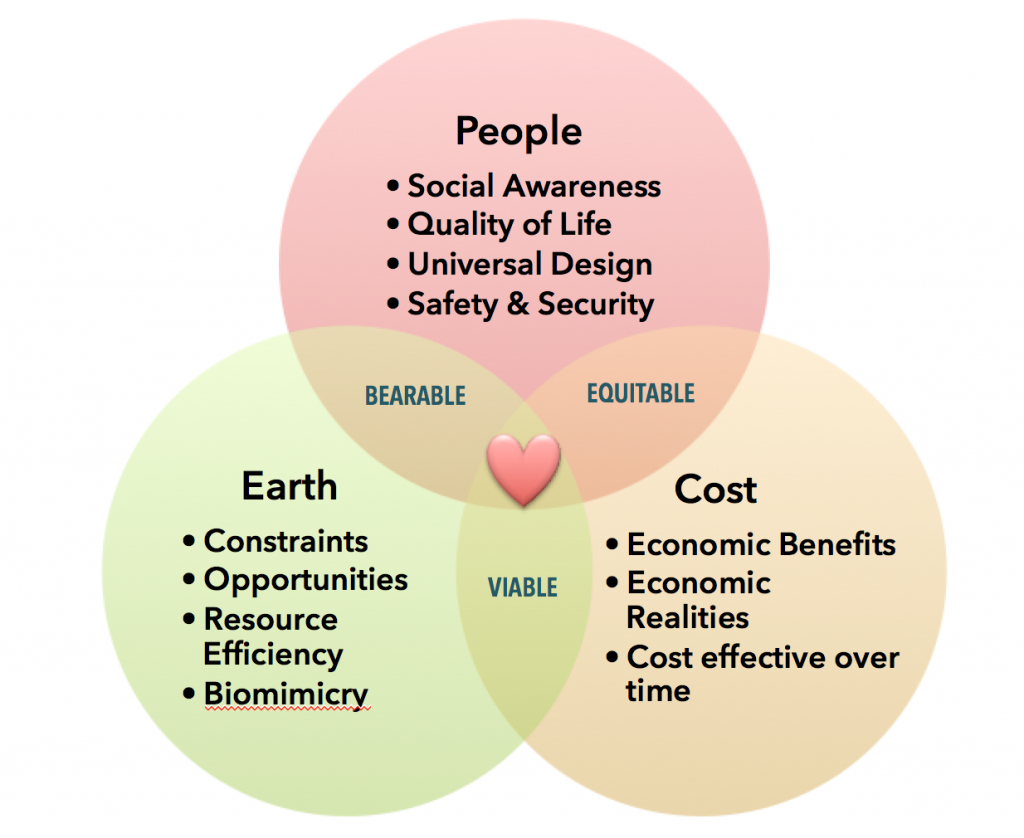

Sustainable House: a house that uses energy and material effectively and efficiently during construction AND in operation, creating as little damage and pollution to natural systems as possible throughout it’s lifecycle.

Energy Efficient House: a house consumes (and wastes) the minimum amount of energy possible (based on budgetary constraints, material/equipment availability, builder capability, owner passion) while maintaining comfort levels for the occupants.

Net Zero Energy House: a NZE house produces as much renewable energy in a year as the purchased energy it consumes. Some states, provinces and cities have already put NZE target dates into legislation — for example, by 2020, all new houses in California must be NZE.

Zero Carbon House: A house that has zero net energy emissions. Carbon emissions generated by onsite or off site fossil fuel use are balanced by the amount of onsite renewable energy production. This is a more established concept in the UK than in North America.

These definitions are general. Here’s how people put them to work in the real world. You can use them to judge how they match your definition of sustainability. All of these program have a good load of free information available to builders and homeowners.

Performance-Based New House Programs

R-2000: This program is available only in Canada. Recently updated, the standard requires builders to have 3rd party verification of the thermal enclosure, the heating and cooling systems, whole-house ventilation and water conservation measures. An R-2000 house uses about 50% less energy for space and water heating than a code-compliant house.

Energy Star for New Houses: To qualify under this program (in Canada and US) builders are required to have 3rd party verification of the thermal enclosure, the heating and cooling systems, water management and lighting and appliance loads. ENERGY STAR certified houses use 15 to 30 percent less energy than code-compliant new houses.

Passive House: Is a performance-based program for energy efficient houses from Germany that has been modified for the range of North American climates. A Passive House can use up to 85% less energy for space heating and 45% less energy for cooling than a code-compliant house. The standard is based on comfort and performance criteria for space heating and cooling only.

LEED for Homes: Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) is a green building rating system that is available in both Canada and the US. Houses built under this standard must meet or exceed benchmarks for in eight areas: site selection, water efficiency, energy efficiency, materials selection, indoor environmental quality (also called indoor air quality), location and linkages, awareness and education, and innovation. Each category has a number of mandatory measures, and a minimum point amount is required for a house to be certified. The more points, the higher the certification: certified, silver, gold or platinum.

Living Building Challenge: This program is focussed mainly on projects at the institutional/commercial scale, not single homes, although there are some certified homes in the program. It is likely the most rigorous formal program out there for quantifying and qualifying sustainability in the built environment.

“The Challenge is comprised of seven performance categories called Petals: Place, Water, Energy, Health & Happiness, Materials, Equity and Beauty. Petals are subdivided into a total of twenty Imperatives, each of which focuses on a specific sphere of influence.” Projects are rated on the number of points they get in each performance category.

Energy Efficiency:

Always the Fundamental Basis of A Sustainable Home

The most important goal, regardless of your favoured or required high-performance house program is very straightforward:

Reduce the overall energy load of the building. This includes space conditioning (heating and cooling, mechanical ventilation, and dehumidification in some climates) domestic hot water and electric ‘baseloads’. Minimizing the energy inputs for the house has a ripple effect that keeps spreading as the years go on: reduced ongoing site environmental damage and pollution from fossil fuel consumption, reduced resource extraction, reduced peak capacity requirements and improved load balancing for utilities, more cost-effective infrastructure for cities and towns.

Fundamentally, you cannot have a sustainable house if it does not address energy efficiency first and foremost. But that shouldn’t be where it ends. Sustainability is more than just energy efficiency –issues like water efficiency needs to be addressed, too. The cool thing is that you can mix and match the standards to make your dream sustainable house. How about a LEED-certified NZE House? Or a Living Challenge-certified Passive House? Best of all sustainable options!

Energy Efficient Stuff , Net Zero Energy Homes

Sustainability Is Not A One-Size-Fits-All Label

I was going to write today about the range of energy efficient and sustainable housing standards and programs that are offered by organizations. But I got sidetracked by an article by Allison Bailes on his Energy Vanguard blog.

I was going to write today about the range of energy efficient and sustainable housing standards and programs that are offered by organizations. But I got sidetracked by an article by Allison Bailes on his Energy Vanguard blog.

In it, he follows up on some harsh criticism of some work done by Alex Wilson of Environmental Building News. Alex had done some number crunching on insulation types and global warming potential (GWP) for an article in 2010. As Allison notes, Alex’s work on this study focussed on a single scenario, with a single material. Which, like anything else, doesn’t exist in the real world. The house exists as a system, in an infrastructure of systems and so, a whole raft of variables need to be considered to determine what’s effective in a given climate with a given set of energy sources, for example.

I’m not going to re-write or paraphrase either Allison’s or Alex’s articles here. If you’re geeky enough to care about the sordid details, you’ll do better to read those yourself. What I do want to point out is that there are no silver-bullet solutions to sustainability, and there are complicated challenges to determining what makes a material, a system, a house, a neighbourhood, a city, sustainable.

I have a couple of f’r instances myself (surprise, surprise).

A heat pump looks/feels/sounds like the best option for a retrofit heating system on a house with an older mid-efficiency oil furnace in Nova Scotia. But not really.

It depends.

Our electricity mix is primarily coal + fuel oil. The emissions are ± 1.1 kg/kWh. The generation and transmission losses across the grid means that less than 30% of the energy available in the fuel is actually usable electricity. This puts a high-efficiency single-processor heat pump at the same efficiency as a new code-compliant oil furnace. So in the big picture immediately, this is not necessarily the best solution in terms of GHG emissions with our current generation mix, but it does anticipate a higher renewables component supplied to the grid.

If, instead, we were looking at a new build, Net Zero Energy Ready project, then it’s a good long-term solution that will drop emissions dramatically, regardless of the generation mix, once the house has site-generated power.

If that new build has spray foam as one of it’s components, we need to know a lot about that material and it’s broadly defined lifecycle cost is to make a fully informed decision about whether it is a sustainable choice for this region with this energy mix or not. That’s a challenge. Who can/wants to crunch those numbers and who can/wants to pay for those numbers to be crunched? What parameters are we going to use? Who decided those?

There’s a great tool that I’ve used for crunching those numbers. The Athena Sustainable Materials Institute has suite of lifecycle cost assessment (LCA) software tools that allows you to look at whole assembly or component LCA. All of these tools are FREE to use. Use ’em and make good choices.

The good news is that you really only have to do these kinds of calculations and analysis for each type of material in your own climate/utility service area for the specific scenarios you will be confronted with. For most designers/builders that’s going to be enough. It’s when you offer your services across several climate and/or utility service areas it’s more challenging.

Please sign up for our newsletter to get all the good stuff.

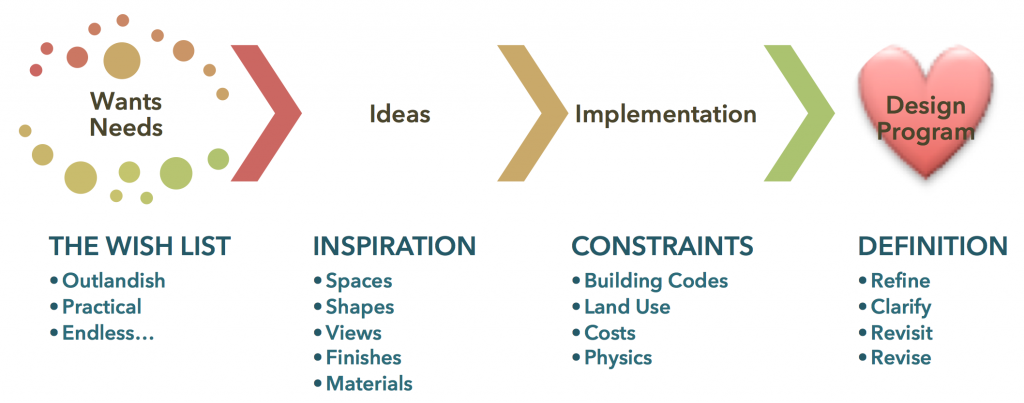

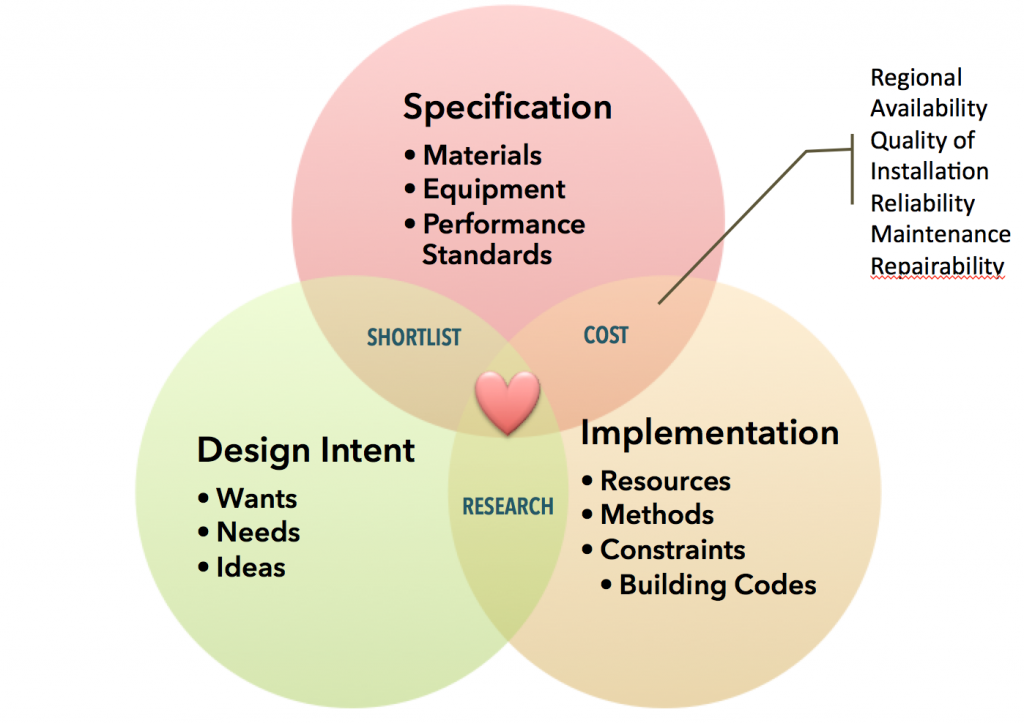

Designing a house or a renovation to an existing house is a complicated process, with many different aspects to consider.

In the broadest sense, it is moving from idea to the plans for the finished project.

All sorts of elements need to be considered, researched and evaluated for every decision to make the design attainable.

Add the elements of sustainability into the mix, just to make it a little more complicated.

The process is really a spiral that loops back and forth, where ideas, obstacles, options, and solutions in one area affect ideas, obstacles, options, and solutions in any other area. Design is about finding the connections and synergies between things that seem like they couldn’t possibly be related.

Yes, yes, it’s me!! Pretty chuffed with myself. Send suggestions for articles, notes about cool projects you’re working on, Net Zero Energy/Deep Energy Retrofit initiatives in your area via this link.

Oy vey.

We are so beyond the theoretical concept of energy-producing houses. The first generation of NZE builders are now at the dial-it-in phase. What worked, what didn’t work, how to improve performance…minimal thermal breaks, maximum thermal envelope, simplified and small mechanical systems.

Somehow I expected that an article pitched and purchased by the Smithsonian would have a little more oomph and research to it.

Just saw this ‘bombshell’ update on one of the LinkedIn groups I belong to: LEED buildings are not necessarily more energy efficient than other buildings built in the same time frame (read more at http://lnkd.in/bksHRbh). This is not too surprising, as the points required to gain any level of LEED certification are broadly distributed across a big spectrum, and a building can reach enough points for certification in many other areas.

When LEED for Homes (LEED-H) first rolled into Canada, the energy benchmark for points was ***below*** the R-2000 standard at the time (2009 LEED for Homes standard was ERS76, R-2000 at the time was ERS80). In fact, the minimum requirements weren’t code compliant in Nova Scotia from Jan 2010 on. Pretty bad showing for a program with the words ‘energy’ and ‘leadership’ in the name. Part of the reason for this was the adoption of the standard US code and technical references. Details @ LEED for Homes Canada in comparison to code and other energy efficient standards in 2009 in this CHBA report.

In 2012, it was changed so that LEED-H gave a project all 8 points available under ‘energy and atmosphere’ if it gained an ERS80 rating, equivalent to the 2005 R-2000 standard (and equivalent to HERS72 in the US), and minimum code compliance in at least 5 provinces. Since then, the R-2000 standard has been boosted to ERS 86 (well, the rating system has been revamped, so that figure is not really relevant any more — but that’s another post or ten to descramble the updated ERS rating). Seems ridiculous that a LEED-H project should get full points for meeting code in most of the country. Industry capability is much higher and LEED builders are likely to be able to move way past that mark. Points should be based on how far the project gets beyond the industry benchmark for energy reduction.

We have builders who are consistently reaching Net Zero Energy in Canada. We have builders who now offer nothing but Net Zero Energy houses. We have R-2000 builders who hit ERS86 or better. We have BuiltGreen builders in Alberta and Ontario rockin’ the low-energy house. In 2012, ENERGY STAR for New Houses builders provided 20% of the new housing stock offered in Ontario. All of these programs step far beyond code compliance. LEED-H could be providing a much more impressive leadership position on energy.

Low Energy Housing , Net Zero Energy Homes , Research Work , Surveys

Survey @ Low Energy Housing Technology Costs

I’m working with the Net-Zero Energy Home Coalition to deliver a survey for Natural Resources Canada. The aim of the survey is to get a better sense of cost-effective design and construction of Low Energy Houses (near NZE, NZE-ready, NZE, any program or standard that you are involved in). Survey is open until midnight, 14 March 2014.

The survey is best filled out by the person who is most familiar with costing the projects.

Here’s the official invite:

The Net-Zero Energy Coalition is seeking costing information from builders across North America who have direct experience building net-zero energy (NZE), net-zero energy ready (NZEr), or near net-zero energy (nNZE) homes. The Coalition is collecting this data in partnership with Natural Resources Canada.

Your participation will help to validate cost effective design and construction of NZE / NZEr / nNZE homes and support the development of guidelines for building these homes.

Individual responses will be kept anonymous – results of the survey will only be communicated in summary form. Participants will receive a copy of the summary report.

This survey will be open until midnight (Eastern Time) on Friday, March 14th. You can access the survey here.

Leave A Comment