Deep Energy Retrofits , Energy Efficient Stuff , Low Energy Housing

Being Visionary in Bridgewater, Nova Scotia

Here’s a success story that is dear to my heart: Bridgewater, NS. Ten years ago, my biz partner and I approached Leon de Vreede, Sustainability Planner for Bridgewater, about an idea for a deep energy retrofit program for houses to be piloted in Bridgewater. We knew his title would make our idea interesting. He liked it, and we worked up a presentation for council, but, well, it was a little too early in their process for anyone to buy in. Truth be told, it was also too early in our process.

Fast forward to 2017, and now, we’re involved with Clean Net Zero, a Deep Energy/Net Zero Retrofit project headed by Clean Foundation, funded by Natural Resources Canada, and ‘hosted’ by the Town of Bridgewater.

Looking to the Future

Clean Net Zero is happening in Bridgewater because there’s vision there. Lots of vision. Plus passion, intelligence, and political will. The town has a 35-year energy plan in place. Here’s some current results from that plan, published on cbc.ca, 1 Dec 2017:

Targets set in 2013, to be met by 2019:

- Energy consumption for Municipal buildings reduced by 25%

- Greenhouse gas emissions from Municipal buildings reduced by 25%

Results in 2017:

- Only 4% more reductions in energy consumption to meet 2019 target

- Greenhouse gas emissions cut by 31% already.

The Town has saved CAD$200,000 in energy costs.

Looking Past Bridgewater

It looks like Leon de Vreede, his team and town council have developed a blueprint for a successful long range energy plan for municipalities. Here’s proof:

Bridgewater Mayor, David Mitchell, attended the Michelin Cities conference in France (Nov 25 – Dec 1 2017). The conference hosts all the communities in the world that have a Michelin plant. He gave a presentation there on the Energize Bridgewater program and sent this news back to his team:

“This afternoon I attended an international press conference of the Mayors for the network of Michelin cities. Media was there from all over the world. This is a direct quote from the delegate from India.

Never did I think I would come to this conference representing the eight million people of my city and have one of our major problems solved by the town of Bridgewater with only 8500 people but their energy plan did just that…

The Energize Bridgewater session was the most well attended of the sessions and from India to Oklahoma, they have questions and see solutions in our plan. We should all be proud of this. It proves the plan is solid. That our community is on the right path and that we will be a resource for the globe going forward. I cannot tell you how proud I am to represent Bridgewater.”

Way to represent, Mayor Dave!

About the Author

Shawna Henderson is CEO of two companies: Blue House Energy, providing online training for the homebuilding industry, and Bfreehomes Design, providing research, design, and consulting services for Net Zero Energy new construction and retrofit projects in Atlantic Canada and beyond.

Deep Energy Retrofits , Design Stuff , Low Energy Housing , Net Zero Energy Homes , Sustainable Home Design

11 Flavours of Sustainable Housing

Keeping track of what’s going on in the world of low-impact, sustainable housing is, and was, a challenge. We did a study for CMHC back in the early 00’s looking for great examples for a series of case studies that required collecting a ton of info on many projects. CMHC published only 3 of 24 case studies, but we had hundreds of submissions to a survey that we sent out to over 7,000 design professionals in 2004 and 2005.

We chose the term ‘low impact housing’ to describe the database because we were looking at the gamut of housing projects affiliated with so many different programs and standards:

- Sustainable

- Ecological

- Factor Four

- Factor Nine

- Green

- Healthy

- Low Emission

- Passivhaus

- Zero Emission

- Zero Energy

- Zero Carbon

The common theme is that the programs, and the projects themselves, went far beyond being energy efficient. They all address a broad range of concerns about environmental impacts throughout the lifecycle of a house – from site selection through design and materials choices, construction, operation, maintenance and demolition.

The Low Impact Housing database is still online, kept up by Sealevel Special Projects because it’s a cool resource.

Go check it out!

Add your project!

Link it to other organizations compiling case studies!

Please sign up for the Bfreehomes newsletter to get all the good stuff.

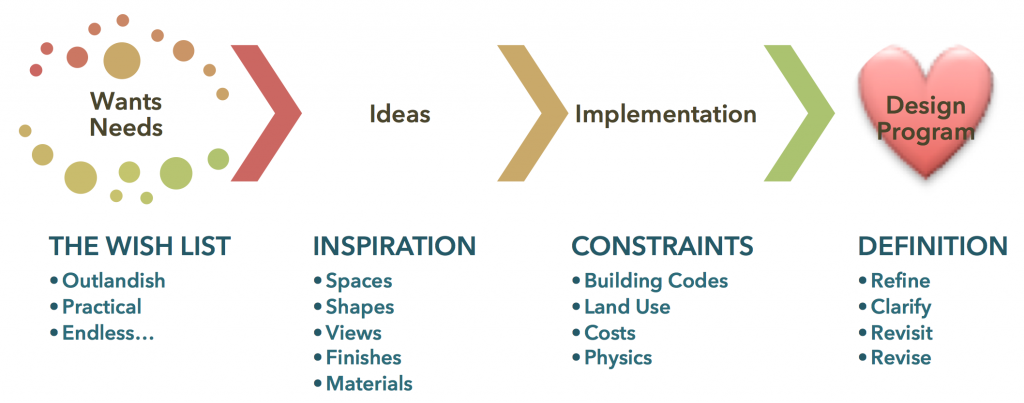

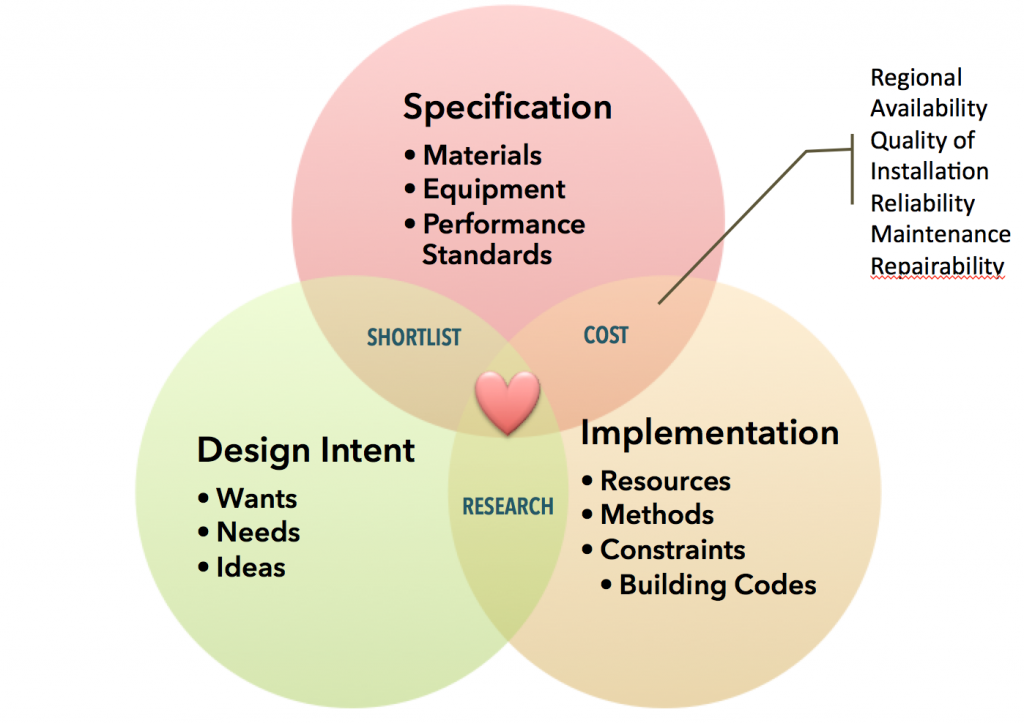

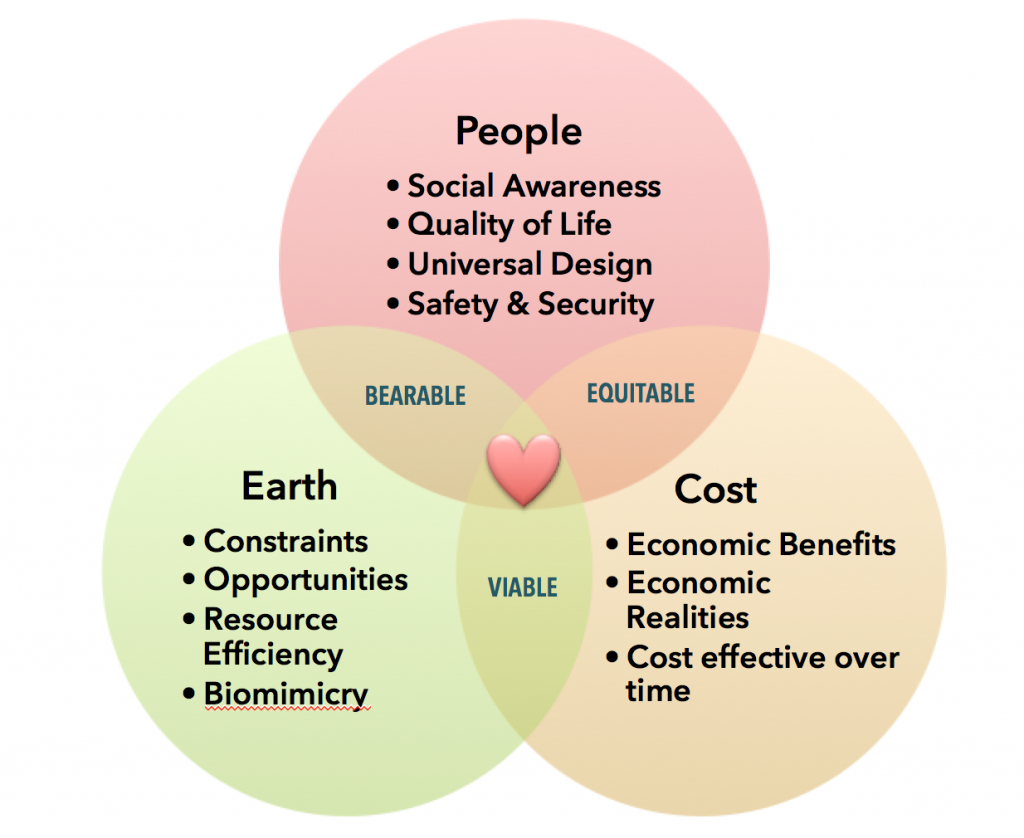

Designing a house or a renovation to an existing house is a complicated process, with many different aspects to consider.

In the broadest sense, it is moving from idea to the plans for the finished project.

All sorts of elements need to be considered, researched and evaluated for every decision to make the design attainable.

Add the elements of sustainability into the mix, just to make it a little more complicated.

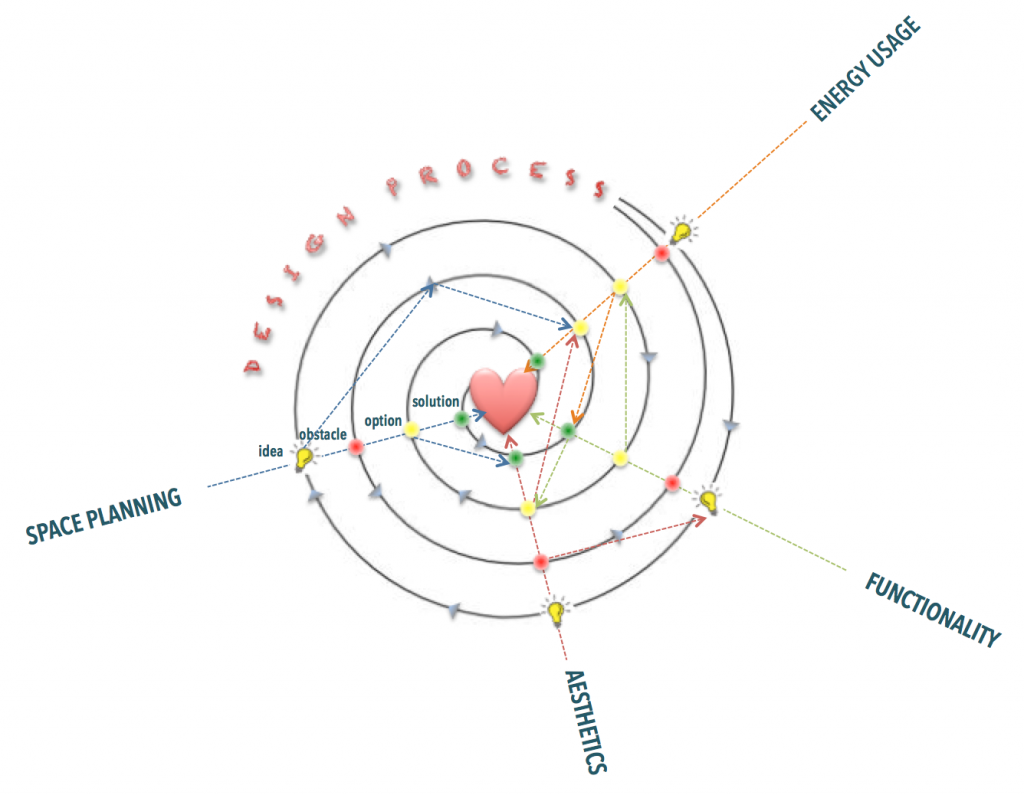

The process is really a spiral that loops back and forth, where ideas, obstacles, options, and solutions in one area affect ideas, obstacles, options, and solutions in any other area. Design is about finding the connections and synergies between things that seem like they couldn’t possibly be related.

Deep Energy Retrofits , Energy Efficient Stuff , Indoor Air Quality

Risks Associated with Poor Spray-Foam Installations

‘Leathery’ spray foam has lost it’s air pockets and is no longer effective. Is it inert in this condition?

A few months ago, I posed a question about spray foam installations and wet wood to some of the forums I belong to.

I got an astounding response — some of it snarky, most of it super helpful. I’m still editing a longer piece that will cover the responses, but in the meantime I ran into this:

Squishy, deflated, leathery 2lb foam. This was installed on the leaky concrete wall of a basement stairwell with a partial foundation, with a connection to an unflashed framed wall above. The house was built in 1836, while the stairwell was obviously a much later addition. The foundation is very wet, the tidelines on the mechanical equipment hitting the 8″ mark, and obvious water markings on the exposed part of the original rubble foundation. After reading all the comments from my original question about spray foam installations and the considered responses, I have to ask myself what spray foam contractor worth their salt would install in such conditions?

The water damage is easily seen throughout the rubble basement walls. The insulation was sprayed onto the top 24 to 36″ of the rubble wall, but has lots of voids and cracks. There is also a wide range of spray consistencies visible — some of the foam looks positively cumulous, while other parts look like smooth lava. Rookie installer? D-I-Y install from a kit system? Who knows — the homeowners purchased this spring and have no records.

From a cursory walk around the perimeter of the house, I knew there would be one fixable source of water leakage into the foundation: over the 175 years, the grade had settled (dramatically in some places), and snow melt and rain water were caught and funneled down into the rubble wall. Straightforward solution to that cause: regrade. Other problems with the foundation, not so straightforward, but we’ll see.

The state of this spray foam made me wonder about health issues, because it had so obviously perished and was dripping this ghastly caramel coloured ooze. There is some field research being done to look at the risks associated with installing spray foam (Field Research to Provide Deeper Look at Spray-Foam Risks – BuildingGreen), but I am not familiar with any studies published on long-term health risks to occupants as a result of crap installations like this one. There are substantiated issues with offgassing immediately after installation, yes, but let’s assume that the product performs as its data sheet indicates, and 24 hours sees most of the offgassing dissipate in a properly done installation.

Water penetration in walls is a problem, period, regardless of the type of insulation that is used, so I’m not freaking out on one type of insulation. From many, many problematic basements, we know what is likely to happen in below-grade frame wall cavities filled with fiberglass batt insulation. When the fiberglass gets wet, it doesn’t drain well or dry out and so causes mold growth given enough warmth. That causes health problems. Cellulose is a total no-go below grade for the same reason. As far as I’m concerned, rockwool is the best option for fibrous insulation below grade. Or spray foam. But only once the foundation is dry. There are so many indoor air quality and eventual structural problems that can be minimized or eliminated by eliminating water leakage into the foundation, and so many that can become exponentially worse by NOT eliminating water leakage into the foundation.

Deep Energy Retrofits , Energy Efficient Stuff , Indoor Air Quality , Stuff that makes me crazy

Damp basement season. It’s coming

What are you going to do about it? Hopefully not install an exhaust only system to pull more humid air into your humid basement.

Don’t. Do. It.

I’ve been discouraging these systems forever, here in Nova Scotia. They don’t reduce humidity levels in basements, but that’s what the marketing infers. What they do is exhaust the humid air from the basement while bringing in humid air from the outside. There is no way to reduce relative humidity levels and stop condensation without a) increasing the ambient air temperature so that it can carry more moisture while at the same time increasing the temperature of all exposed (or first condensing) surfaces or b) stripping moisture out of the ambient air (that’s what a dehumidifier does — oh, wait, that’s the market these exhaust only systems are muscling in on). In reality, the best way to deal with humid basements is to #1 Find the moisture source(s), and #2 Eliminate them. That’s the straight up, bottom line, end of story.

Moisture sources like open sumps are the problem — sealing this off before doing anything else will go a long way to reducing the moisture level in your basement or crawlspace. Note the white efflorescence on the wall — that’s salt crystals left behind from moisture migrating through the wall.

Open sumps, cracks in concrete that allow bulk water into the basement, these are pretty obvious sources. Less obvious sources include crappy drainage at the foundation, damaged or non-existent drainpipe leaders, high water tables.

Then there’s the fact that cooler surfaces cause moisture to condense out of warm, humid air. Concrete or masonry, present in most basements, are terrific first condensing surfaces. Insulating concrete and masonry can help to reduce the extent of condensation. But only if all moisture sources are dealt with so there’s trapping of more moisture in the basement…so back to #1 above.

Read this blog post by Allison Bailes at Energy Vanguard if you want more details about the pitfalls of exhaust-only systems and a fantastic in-depth explanation of why they won’t, don’t, can’t work in basements. Although he references New Orleans specifically, the physics that lead to problems with humid air and cold surfaces, along with the need to eliminate moisture sources in basements and crawlspaces are the same everywhere. The severity of the problem is related to the climate zone and the condition of the basement.

Deep Energy Retrofits , Energy Efficient Stuff , Low Energy Housing

Invited to present at WREN (World Renewable Energy Network) conference

The WREN Conference invitation came because I was invited to write a chapter in a book on Sustainable Buildings back in 2012. The book (Sustainability, Energy and Architecture: Case Studies in Realizing Green Buildings) was published last year (http://bit.ly/OXVl0k). The chapter I wrote was ‘Deep Green and Comfortable’, focussing on energy savings to be had by carrying out deep energy retrofits on existing houses.

The paper I’m writing for the conference expands somewhat on that idea, and looks at the missing part in many discussions that I’ve had in the field, with clients, renovators, lenders and other stakeholders: proving the value of deep energy retrofits. Not just for the current homeowner, but for future homeowners and for the municipality/community.

The idea came out of one particularly frustrating discussion with a potential contractor for one of my renovation clients. Note that this was a contractor who was bidding on a job that had already been specified. The client wanted to stay in the 100 year old house (location was spectacular, structure was sound, a phased deep energy retrofit was completely reasonable option). We were recapping the details of phase 1, when the contractor put down his pen and calmly told (my) client that renovating was not the right option. That the cost was likely to be more than 30% of the appraised value of the house, and therefore not a good economic decision.

Then he continued, telling (my) client that their best bet was to go out to the suburbs and buy/build new.

This, I thought, was not cool. The client’s preference — to stay in the house, and the strategy we had landed on — to phase the retrofit over 5 years, was clearly articulated, with modelled energy reductions, projected fuel costs (they were on oil, we were looking at a heat pump after major envelope work) and rough order costings showing payback and ROI. Apparently that didn’t make much of a dint in the contractor’s view, even though he had been briefed on the project and asked to review the design program and ask me any questions before the meeting.

I wondered where he pulled the 30% figure from, politely. It was a ‘rule of thumb’, he told me. I didn’t ask where his thumb had been, but I did ask him to back up the rule of thumb with some concrete information, which never came — neither did the quote.

So then I started thinking about the inherent value of established neighbourhoods with infrastructure vs the cost of greenfield development, and then I started mashing that together with the value of the resources tied up in an existing house, and the cost of retrofit vs. the cost of new construction and I got all jumped up about research and proving the case for deep energy retrofits.

For your entertainment, I’ll be blogging bits and pieces on this over the next few months…WREN conference is in August.

Leave A Comment