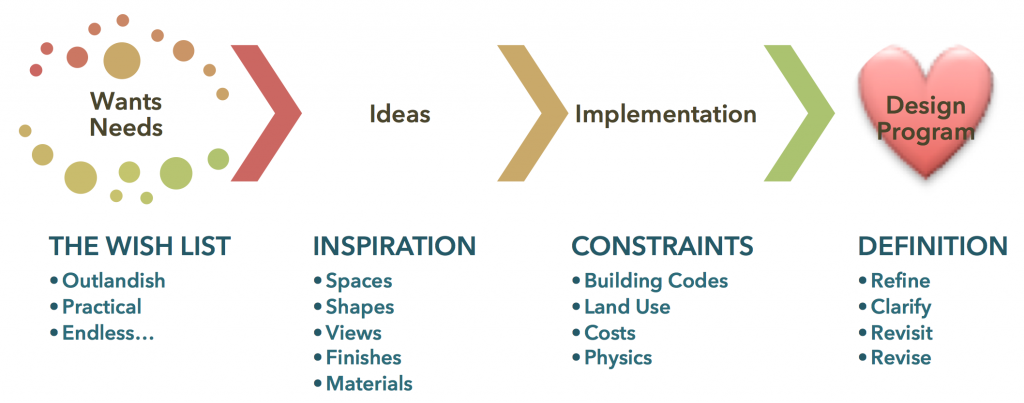

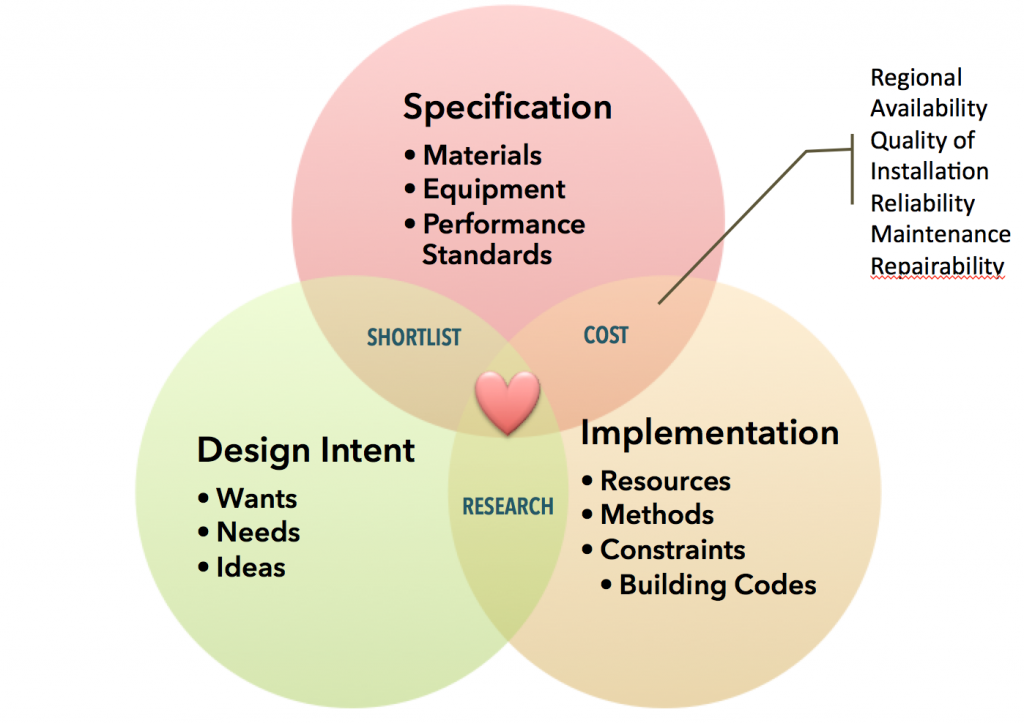

Designing a house or a renovation to an existing house is a complicated process, with many different aspects to consider.

In the broadest sense, it is moving from idea to the plans for the finished project.

All sorts of elements need to be considered, researched and evaluated for every decision to make the design attainable.

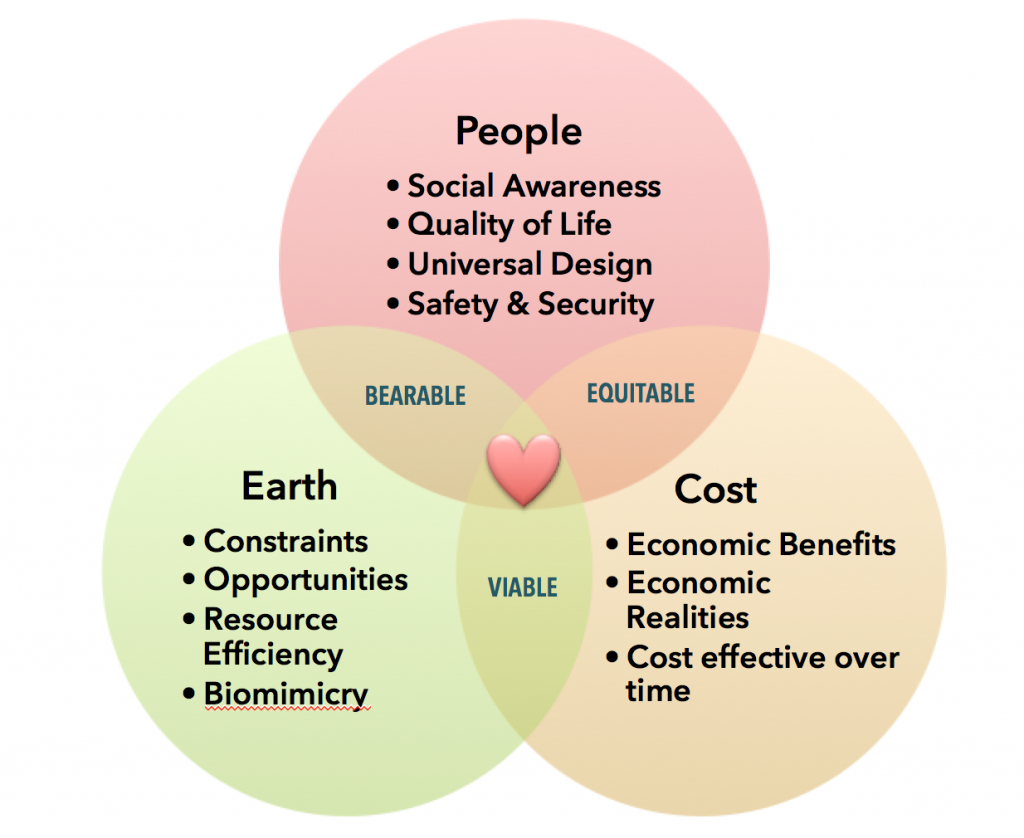

Add the elements of sustainability into the mix, just to make it a little more complicated.

The process is really a spiral that loops back and forth, where ideas, obstacles, options, and solutions in one area affect ideas, obstacles, options, and solutions in any other area. Design is about finding the connections and synergies between things that seem like they couldn’t possibly be related.

Low Energy Housing , Net Zero Energy Homes , Stuff that makes me crazy

How zero is net zero…what’s not changing?

So there’s lots of excellent work and capacity building going on and Net Zero Energy and Low Energy and High Performance houses are being designed and built throughout North America. Innovation and forward thinking abound. It’s all very exciting. But there’s a place past which most builders, designers, and homeowners will not go: beyond low-flow plumbing fixtures, specifically toilets. Massive infrastructure has made it pretty convenient to not think about the consequences of flush toilets. Sure, there are problems with effluent and e.coli and we have to treat water severely before it can be classed as ‘clean’ once we flush it, but there are engineering solutions for that, and there’s lots of money tied up in that, and this system works just fine, thanks, with a few extra jolts of chlorine added every once in a while.

But really, no. There are big issues. This is not a good version of an open system. Piped water is a great convenience and a massive boon to public health, at the same time that it’s a disaster for the environment.

Water usage and access to potable water is in my mind a lot right now, with water rate hikes, and low-income households in Detroit having their water turned off due to one missed payment (yet 80% of the unpaid bills are corporate customers), and the looming potential of privatization of water resources. Tank Girl anyone?

Water shut-offs at the city scale, like what’s happening in Detroit (hey, kick ’em while they’re down, whydoncha?), are likely precursors to major health problems, to homes being made uninhabitable, and to state-sanctioned removal of children from their homes. How is that cost-effective? What are people going to do? Where are they going to go (in so many ways, where are they going to go), and how does the city expect to garner property taxes out of more derelict, abandoned houses? It’s a painful situation where solutions need to be found, and quickly, but this plays out quickly in my head as a worsening situation not an improving one, not even in the short run.

This article, by Lloyd Alter, managing editor of Treehugger, does a good job of dissecting problems with the North American approach to piped water and poop. I like his observation that the modern bathroom hasn’t changed much since 1910: small room, porcelain fixtures, line everything up in a row to use less pipe. Done.

Ya, except is this the best way to do it?

Critical analysis would indicate not: just from a health point of view, flushing a toilet sends reams of bacteria into the air. And sinks are right beside toilets. And toothbrushes are right beside sinks. Ew.

And there’s more: toilets are designed for sitting, we’re designed for squatting…ergonomics 101 have not been applied to the standard bathroom layout or fixture design. But we do have have an engineering solution.

But flushing is the big thing that circles back to my concerns about piped potable water usage and energy use and costs (not to mention the burden on aquifers and such): flush toilets result in millions of gallons of clean, potable (ie, drinkable) water contaminated, churned up and redistributed for your swimming pleasure. Ew. It wouldn’t be quite so bad if the blackwater (toilets) and greywater (pretty much everything else) were separately treated. Then at least the lightly contaminated greywater could be treated in a different manner that quite possibly would be less energy intensive, bringing down the overall amount of energy required to treat water (from Alter’s article: 10 bn litres of sewage/day in England and Wales requires ±6.3 GW hours of energy to treat, nearly 1% of daily electrical consumption for the two countries).

What if there were no blac kwater? If there were no flushing…

kwater? If there were no flushing…

Compost toilets have been around for a long time — I first read about them in my cherished 1981 first edition of ‘More Homes and Other Garbage: Designs for Self-sufficient Living‘. Clivus Multrum was then, and still is, the Cadillac of Composting Crappers.

It could be time to re-write Witold Rybczynski’s classic from the ’70s ‘Stop the Five Gallon Flush‘ (That book was out of McGill, it was brilliant, and yes, I have a copy), as ‘Stop the Flush’.

Except of course, people would be responsible for their own shit.

That could be awkward.

Or it could be a re-learning of how open systems work — you have an environment, there’s input from the environment, there’s throughput, and there’s output back into environment, feedback comes from the environment and allows for changes that allow for survival and growth.

THAT would be fine.

Just saw this ‘bombshell’ update on one of the LinkedIn groups I belong to: LEED buildings are not necessarily more energy efficient than other buildings built in the same time frame (read more at http://lnkd.in/bksHRbh). This is not too surprising, as the points required to gain any level of LEED certification are broadly distributed across a big spectrum, and a building can reach enough points for certification in many other areas.

When LEED for Homes (LEED-H) first rolled into Canada, the energy benchmark for points was ***below*** the R-2000 standard at the time (2009 LEED for Homes standard was ERS76, R-2000 at the time was ERS80). In fact, the minimum requirements weren’t code compliant in Nova Scotia from Jan 2010 on. Pretty bad showing for a program with the words ‘energy’ and ‘leadership’ in the name. Part of the reason for this was the adoption of the standard US code and technical references. Details @ LEED for Homes Canada in comparison to code and other energy efficient standards in 2009 in this CHBA report.

In 2012, it was changed so that LEED-H gave a project all 8 points available under ‘energy and atmosphere’ if it gained an ERS80 rating, equivalent to the 2005 R-2000 standard (and equivalent to HERS72 in the US), and minimum code compliance in at least 5 provinces. Since then, the R-2000 standard has been boosted to ERS 86 (well, the rating system has been revamped, so that figure is not really relevant any more — but that’s another post or ten to descramble the updated ERS rating). Seems ridiculous that a LEED-H project should get full points for meeting code in most of the country. Industry capability is much higher and LEED builders are likely to be able to move way past that mark. Points should be based on how far the project gets beyond the industry benchmark for energy reduction.

We have builders who are consistently reaching Net Zero Energy in Canada. We have builders who now offer nothing but Net Zero Energy houses. We have R-2000 builders who hit ERS86 or better. We have BuiltGreen builders in Alberta and Ontario rockin’ the low-energy house. In 2012, ENERGY STAR for New Houses builders provided 20% of the new housing stock offered in Ontario. All of these programs step far beyond code compliance. LEED-H could be providing a much more impressive leadership position on energy.

Low Energy Housing , Net Zero Energy Homes , Research Work , Surveys

Survey @ Low Energy Housing Technology Costs

I’m working with the Net-Zero Energy Home Coalition to deliver a survey for Natural Resources Canada. The aim of the survey is to get a better sense of cost-effective design and construction of Low Energy Houses (near NZE, NZE-ready, NZE, any program or standard that you are involved in). Survey is open until midnight, 14 March 2014.

The survey is best filled out by the person who is most familiar with costing the projects.

Here’s the official invite:

The Net-Zero Energy Coalition is seeking costing information from builders across North America who have direct experience building net-zero energy (NZE), net-zero energy ready (NZEr), or near net-zero energy (nNZE) homes. The Coalition is collecting this data in partnership with Natural Resources Canada.

Your participation will help to validate cost effective design and construction of NZE / NZEr / nNZE homes and support the development of guidelines for building these homes.

Individual responses will be kept anonymous – results of the survey will only be communicated in summary form. Participants will receive a copy of the summary report.

This survey will be open until midnight (Eastern Time) on Friday, March 14th. You can access the survey here.

Leave A Comment