Deep Energy Retrofits , Energy Efficient Stuff , Low Energy Housing

Being Visionary in Bridgewater, Nova Scotia

Here’s a success story that is dear to my heart: Bridgewater, NS. Ten years ago, my biz partner and I approached Leon de Vreede, Sustainability Planner for Bridgewater, about an idea for a deep energy retrofit program for houses to be piloted in Bridgewater. We knew his title would make our idea interesting. He liked it, and we worked up a presentation for council, but, well, it was a little too early in their process for anyone to buy in. Truth be told, it was also too early in our process.

Fast forward to 2017, and now, we’re involved with Clean Net Zero, a Deep Energy/Net Zero Retrofit project headed by Clean Foundation, funded by Natural Resources Canada, and ‘hosted’ by the Town of Bridgewater.

Looking to the Future

Clean Net Zero is happening in Bridgewater because there’s vision there. Lots of vision. Plus passion, intelligence, and political will. The town has a 35-year energy plan in place. Here’s some current results from that plan, published on cbc.ca, 1 Dec 2017:

Targets set in 2013, to be met by 2019:

- Energy consumption for Municipal buildings reduced by 25%

- Greenhouse gas emissions from Municipal buildings reduced by 25%

Results in 2017:

- Only 4% more reductions in energy consumption to meet 2019 target

- Greenhouse gas emissions cut by 31% already.

The Town has saved CAD$200,000 in energy costs.

Looking Past Bridgewater

It looks like Leon de Vreede, his team and town council have developed a blueprint for a successful long range energy plan for municipalities. Here’s proof:

Bridgewater Mayor, David Mitchell, attended the Michelin Cities conference in France (Nov 25 – Dec 1 2017). The conference hosts all the communities in the world that have a Michelin plant. He gave a presentation there on the Energize Bridgewater program and sent this news back to his team:

“This afternoon I attended an international press conference of the Mayors for the network of Michelin cities. Media was there from all over the world. This is a direct quote from the delegate from India.

Never did I think I would come to this conference representing the eight million people of my city and have one of our major problems solved by the town of Bridgewater with only 8500 people but their energy plan did just that…

The Energize Bridgewater session was the most well attended of the sessions and from India to Oklahoma, they have questions and see solutions in our plan. We should all be proud of this. It proves the plan is solid. That our community is on the right path and that we will be a resource for the globe going forward. I cannot tell you how proud I am to represent Bridgewater.”

Way to represent, Mayor Dave!

About the Author

Shawna Henderson is CEO of two companies: Blue House Energy, providing online training for the homebuilding industry, and Bfreehomes Design, providing research, design, and consulting services for Net Zero Energy new construction and retrofit projects in Atlantic Canada and beyond.

Deep Energy Retrofits , Design Stuff , Low Energy Housing , Net Zero Energy Homes , Sustainable Home Design

11 Flavours of Sustainable Housing

Keeping track of what’s going on in the world of low-impact, sustainable housing is, and was, a challenge. We did a study for CMHC back in the early 00’s looking for great examples for a series of case studies that required collecting a ton of info on many projects. CMHC published only 3 of 24 case studies, but we had hundreds of submissions to a survey that we sent out to over 7,000 design professionals in 2004 and 2005.

We chose the term ‘low impact housing’ to describe the database because we were looking at the gamut of housing projects affiliated with so many different programs and standards:

- Sustainable

- Ecological

- Factor Four

- Factor Nine

- Green

- Healthy

- Low Emission

- Passivhaus

- Zero Emission

- Zero Energy

- Zero Carbon

The common theme is that the programs, and the projects themselves, went far beyond being energy efficient. They all address a broad range of concerns about environmental impacts throughout the lifecycle of a house – from site selection through design and materials choices, construction, operation, maintenance and demolition.

The Low Impact Housing database is still online, kept up by Sealevel Special Projects because it’s a cool resource.

Go check it out!

Add your project!

Link it to other organizations compiling case studies!

Please sign up for the Bfreehomes newsletter to get all the good stuff.

Energy Efficient Stuff , Low Energy Housing , Net Zero Energy Homes , Sustainable Home Design

What Do You Get When You Mash Up A Refrigerator Box, A Trailer, A Sleeping Bag, and a Thermos?

Notice the steep pitched metal roof. The snow has slid and/or melted off the peak, but there’s still a deep blanket on the rest of the roof, meaning there’s great air sealing and a lot of insulation under it!

You get a Tiny House that works in cold climates!

In 2015, I did a presentation for the NS Tiny House Movement Meet Up group.

I flagged some of the issues I saw in terms of cold climates and energy efficiency and how to solve them for tiny houses.

Here’s the presentation. I’m planning on expanding it and adding a couple of case studies, along with a voice over and an interview or two.

Let me know what information you’d like to have added!

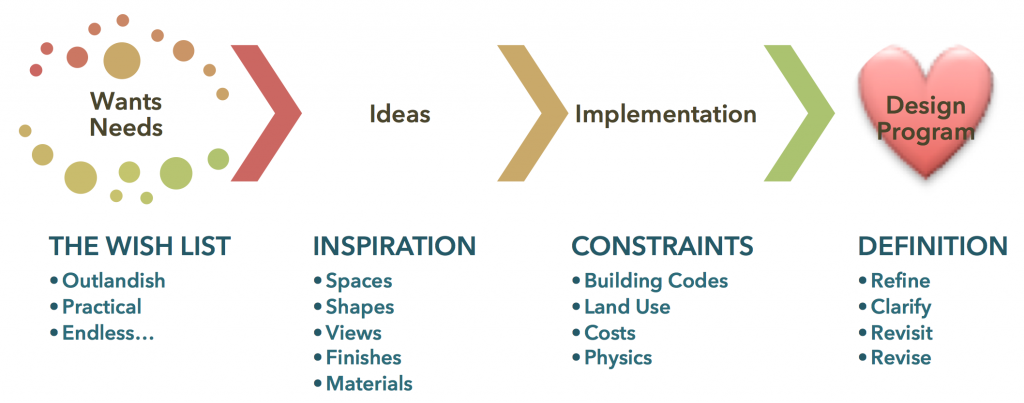

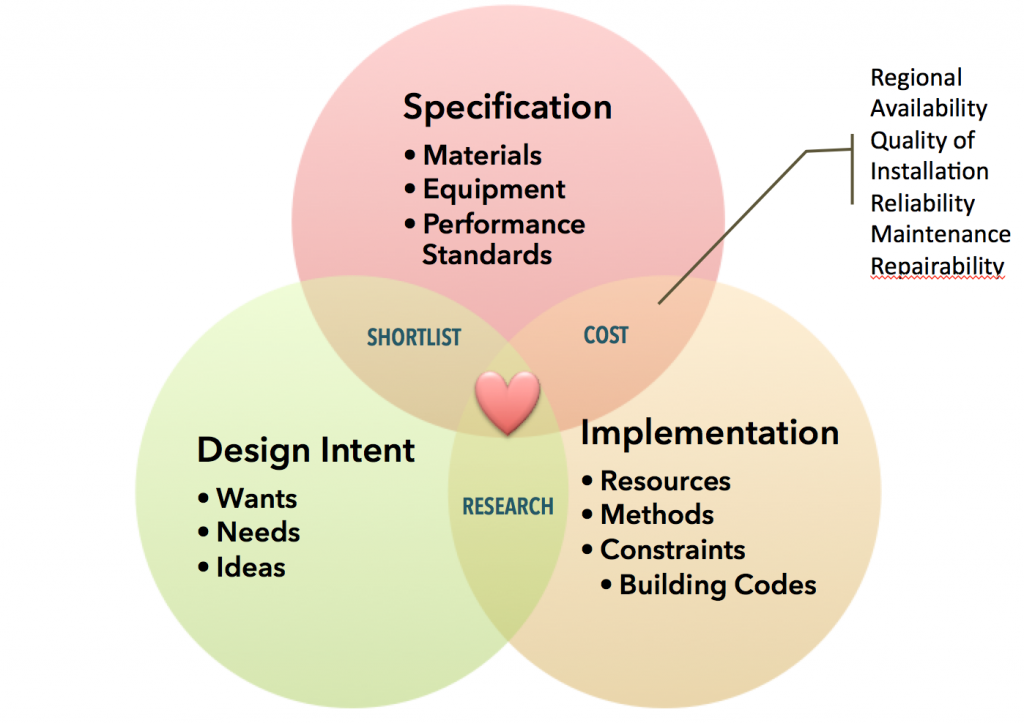

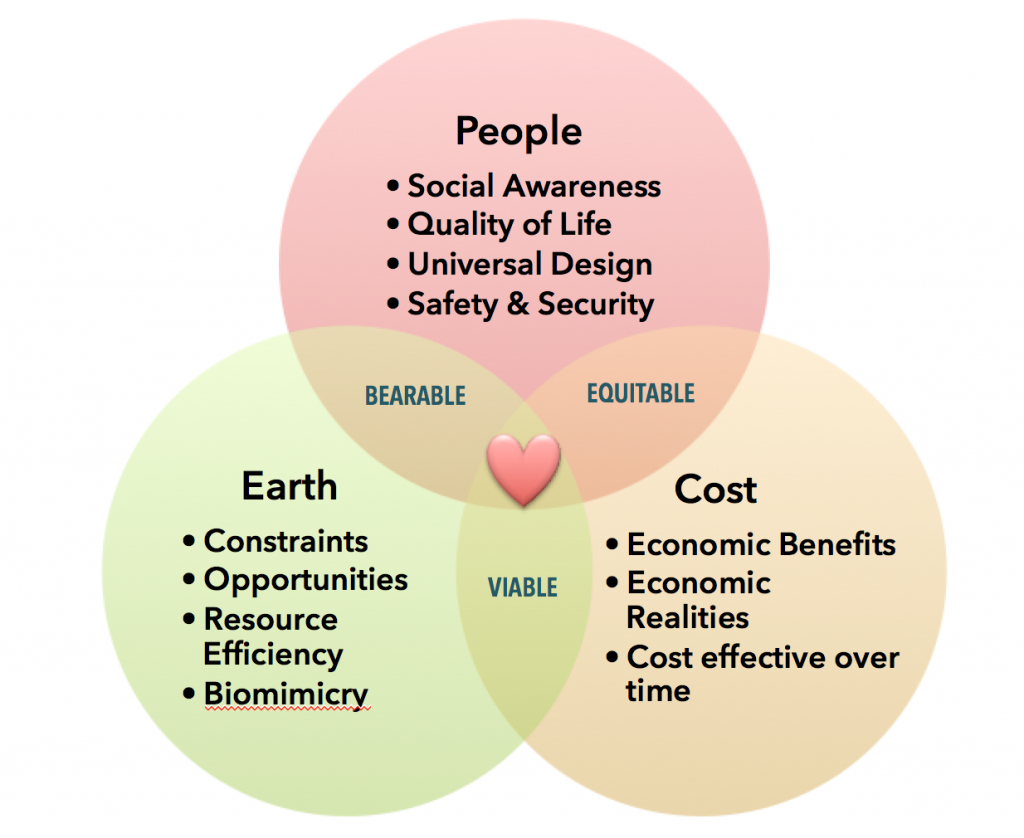

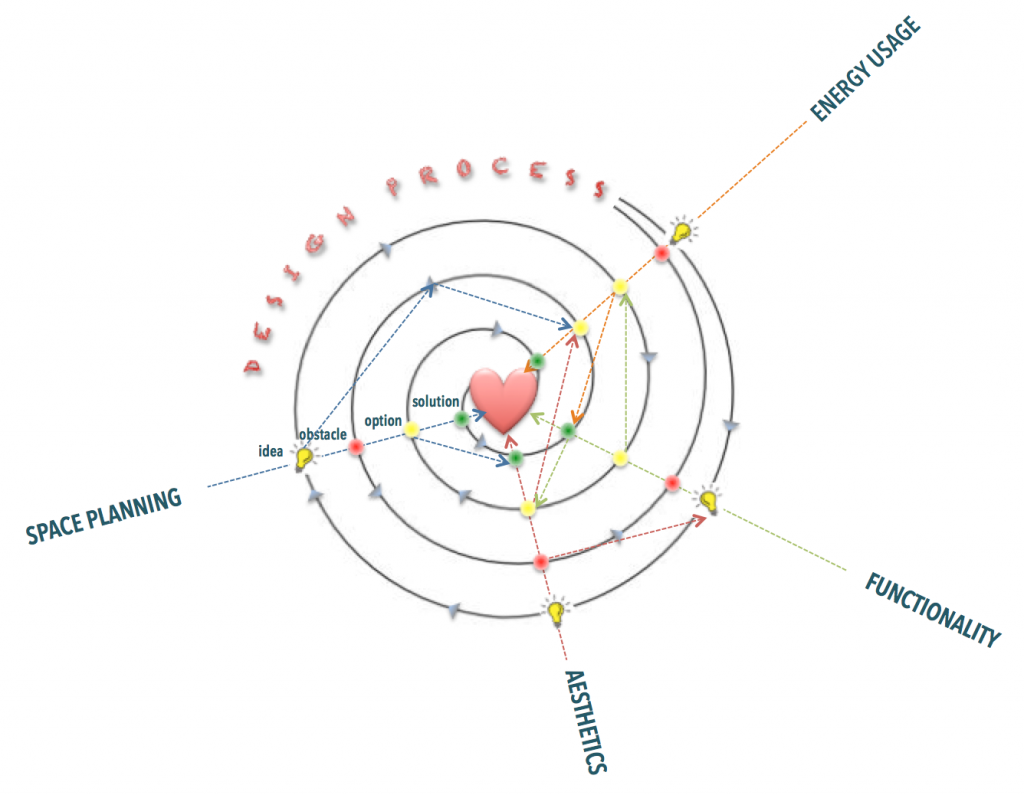

Designing a house or a renovation to an existing house is a complicated process, with many different aspects to consider.

In the broadest sense, it is moving from idea to the plans for the finished project.

All sorts of elements need to be considered, researched and evaluated for every decision to make the design attainable.

Add the elements of sustainability into the mix, just to make it a little more complicated.

The process is really a spiral that loops back and forth, where ideas, obstacles, options, and solutions in one area affect ideas, obstacles, options, and solutions in any other area. Design is about finding the connections and synergies between things that seem like they couldn’t possibly be related.

Low Energy Housing , Net Zero Energy Homes , Stuff that makes me crazy

How zero is net zero…what’s not changing?

So there’s lots of excellent work and capacity building going on and Net Zero Energy and Low Energy and High Performance houses are being designed and built throughout North America. Innovation and forward thinking abound. It’s all very exciting. But there’s a place past which most builders, designers, and homeowners will not go: beyond low-flow plumbing fixtures, specifically toilets. Massive infrastructure has made it pretty convenient to not think about the consequences of flush toilets. Sure, there are problems with effluent and e.coli and we have to treat water severely before it can be classed as ‘clean’ once we flush it, but there are engineering solutions for that, and there’s lots of money tied up in that, and this system works just fine, thanks, with a few extra jolts of chlorine added every once in a while.

But really, no. There are big issues. This is not a good version of an open system. Piped water is a great convenience and a massive boon to public health, at the same time that it’s a disaster for the environment.

Water usage and access to potable water is in my mind a lot right now, with water rate hikes, and low-income households in Detroit having their water turned off due to one missed payment (yet 80% of the unpaid bills are corporate customers), and the looming potential of privatization of water resources. Tank Girl anyone?

Water shut-offs at the city scale, like what’s happening in Detroit (hey, kick ’em while they’re down, whydoncha?), are likely precursors to major health problems, to homes being made uninhabitable, and to state-sanctioned removal of children from their homes. How is that cost-effective? What are people going to do? Where are they going to go (in so many ways, where are they going to go), and how does the city expect to garner property taxes out of more derelict, abandoned houses? It’s a painful situation where solutions need to be found, and quickly, but this plays out quickly in my head as a worsening situation not an improving one, not even in the short run.

This article, by Lloyd Alter, managing editor of Treehugger, does a good job of dissecting problems with the North American approach to piped water and poop. I like his observation that the modern bathroom hasn’t changed much since 1910: small room, porcelain fixtures, line everything up in a row to use less pipe. Done.

Ya, except is this the best way to do it?

Critical analysis would indicate not: just from a health point of view, flushing a toilet sends reams of bacteria into the air. And sinks are right beside toilets. And toothbrushes are right beside sinks. Ew.

And there’s more: toilets are designed for sitting, we’re designed for squatting…ergonomics 101 have not been applied to the standard bathroom layout or fixture design. But we do have have an engineering solution.

But flushing is the big thing that circles back to my concerns about piped potable water usage and energy use and costs (not to mention the burden on aquifers and such): flush toilets result in millions of gallons of clean, potable (ie, drinkable) water contaminated, churned up and redistributed for your swimming pleasure. Ew. It wouldn’t be quite so bad if the blackwater (toilets) and greywater (pretty much everything else) were separately treated. Then at least the lightly contaminated greywater could be treated in a different manner that quite possibly would be less energy intensive, bringing down the overall amount of energy required to treat water (from Alter’s article: 10 bn litres of sewage/day in England and Wales requires ±6.3 GW hours of energy to treat, nearly 1% of daily electrical consumption for the two countries).

What if there were no blac kwater? If there were no flushing…

kwater? If there were no flushing…

Compost toilets have been around for a long time — I first read about them in my cherished 1981 first edition of ‘More Homes and Other Garbage: Designs for Self-sufficient Living‘. Clivus Multrum was then, and still is, the Cadillac of Composting Crappers.

It could be time to re-write Witold Rybczynski’s classic from the ’70s ‘Stop the Five Gallon Flush‘ (That book was out of McGill, it was brilliant, and yes, I have a copy), as ‘Stop the Flush’.

Except of course, people would be responsible for their own shit.

That could be awkward.

Or it could be a re-learning of how open systems work — you have an environment, there’s input from the environment, there’s throughput, and there’s output back into environment, feedback comes from the environment and allows for changes that allow for survival and growth.

THAT would be fine.

Deep Energy Retrofits , Energy Efficient Stuff , Low Energy Housing

Invited to present at WREN (World Renewable Energy Network) conference

The WREN Conference invitation came because I was invited to write a chapter in a book on Sustainable Buildings back in 2012. The book (Sustainability, Energy and Architecture: Case Studies in Realizing Green Buildings) was published last year (http://bit.ly/OXVl0k). The chapter I wrote was ‘Deep Green and Comfortable’, focussing on energy savings to be had by carrying out deep energy retrofits on existing houses.

The paper I’m writing for the conference expands somewhat on that idea, and looks at the missing part in many discussions that I’ve had in the field, with clients, renovators, lenders and other stakeholders: proving the value of deep energy retrofits. Not just for the current homeowner, but for future homeowners and for the municipality/community.

The idea came out of one particularly frustrating discussion with a potential contractor for one of my renovation clients. Note that this was a contractor who was bidding on a job that had already been specified. The client wanted to stay in the 100 year old house (location was spectacular, structure was sound, a phased deep energy retrofit was completely reasonable option). We were recapping the details of phase 1, when the contractor put down his pen and calmly told (my) client that renovating was not the right option. That the cost was likely to be more than 30% of the appraised value of the house, and therefore not a good economic decision.

Then he continued, telling (my) client that their best bet was to go out to the suburbs and buy/build new.

This, I thought, was not cool. The client’s preference — to stay in the house, and the strategy we had landed on — to phase the retrofit over 5 years, was clearly articulated, with modelled energy reductions, projected fuel costs (they were on oil, we were looking at a heat pump after major envelope work) and rough order costings showing payback and ROI. Apparently that didn’t make much of a dint in the contractor’s view, even though he had been briefed on the project and asked to review the design program and ask me any questions before the meeting.

I wondered where he pulled the 30% figure from, politely. It was a ‘rule of thumb’, he told me. I didn’t ask where his thumb had been, but I did ask him to back up the rule of thumb with some concrete information, which never came — neither did the quote.

So then I started thinking about the inherent value of established neighbourhoods with infrastructure vs the cost of greenfield development, and then I started mashing that together with the value of the resources tied up in an existing house, and the cost of retrofit vs. the cost of new construction and I got all jumped up about research and proving the case for deep energy retrofits.

For your entertainment, I’ll be blogging bits and pieces on this over the next few months…WREN conference is in August.

Just saw this ‘bombshell’ update on one of the LinkedIn groups I belong to: LEED buildings are not necessarily more energy efficient than other buildings built in the same time frame (read more at http://lnkd.in/bksHRbh). This is not too surprising, as the points required to gain any level of LEED certification are broadly distributed across a big spectrum, and a building can reach enough points for certification in many other areas.

When LEED for Homes (LEED-H) first rolled into Canada, the energy benchmark for points was ***below*** the R-2000 standard at the time (2009 LEED for Homes standard was ERS76, R-2000 at the time was ERS80). In fact, the minimum requirements weren’t code compliant in Nova Scotia from Jan 2010 on. Pretty bad showing for a program with the words ‘energy’ and ‘leadership’ in the name. Part of the reason for this was the adoption of the standard US code and technical references. Details @ LEED for Homes Canada in comparison to code and other energy efficient standards in 2009 in this CHBA report.

In 2012, it was changed so that LEED-H gave a project all 8 points available under ‘energy and atmosphere’ if it gained an ERS80 rating, equivalent to the 2005 R-2000 standard (and equivalent to HERS72 in the US), and minimum code compliance in at least 5 provinces. Since then, the R-2000 standard has been boosted to ERS 86 (well, the rating system has been revamped, so that figure is not really relevant any more — but that’s another post or ten to descramble the updated ERS rating). Seems ridiculous that a LEED-H project should get full points for meeting code in most of the country. Industry capability is much higher and LEED builders are likely to be able to move way past that mark. Points should be based on how far the project gets beyond the industry benchmark for energy reduction.

We have builders who are consistently reaching Net Zero Energy in Canada. We have builders who now offer nothing but Net Zero Energy houses. We have R-2000 builders who hit ERS86 or better. We have BuiltGreen builders in Alberta and Ontario rockin’ the low-energy house. In 2012, ENERGY STAR for New Houses builders provided 20% of the new housing stock offered in Ontario. All of these programs step far beyond code compliance. LEED-H could be providing a much more impressive leadership position on energy.

Low Energy Housing , Net Zero Energy Homes , Research Work , Surveys

Survey @ Low Energy Housing Technology Costs

I’m working with the Net-Zero Energy Home Coalition to deliver a survey for Natural Resources Canada. The aim of the survey is to get a better sense of cost-effective design and construction of Low Energy Houses (near NZE, NZE-ready, NZE, any program or standard that you are involved in). Survey is open until midnight, 14 March 2014.

The survey is best filled out by the person who is most familiar with costing the projects.

Here’s the official invite:

The Net-Zero Energy Coalition is seeking costing information from builders across North America who have direct experience building net-zero energy (NZE), net-zero energy ready (NZEr), or near net-zero energy (nNZE) homes. The Coalition is collecting this data in partnership with Natural Resources Canada.

Your participation will help to validate cost effective design and construction of NZE / NZEr / nNZE homes and support the development of guidelines for building these homes.

Individual responses will be kept anonymous – results of the survey will only be communicated in summary form. Participants will receive a copy of the summary report.

This survey will be open until midnight (Eastern Time) on Friday, March 14th. You can access the survey here.

Leave A Comment